The OWASP Top Ten provides an essential framework for identifying the most critical security risks facing web applications, IoT devices, and embedded systems. For manufacturers targeting the European market, this list is no longer just a set of best practices. It has become a direct map to the security obligations mandated by the EU’s Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), making it a cornerstone of modern product security and compliance strategy. Understanding and addressing these vulnerabilities is fundamental to building secure and resilient products.

This definitive guide breaks down each of the ten vulnerabilities with a focus on practical application. We move beyond abstract definitions to provide real-world examples, particularly within the unique context of IoT and embedded firmware where the stakes are often higher. You will learn actionable techniques for detection and mitigation, connecting each vulnerability to its corresponding CRA requirements for vulnerability management, secure updates, and documentation.

Throughout this roundup, we will explore how a compliance platform can operationalise these security principles, transforming complex requirements into an actionable, audit-ready plan. Prepare to move beyond theory and into the practical steps required to build secure, resilient, and compliant digital products for the EU market and beyond. This article is your roadmap for turning the OWASP Top Ten from a checklist into a core component of your secure-by-design process.

1. A01:2021 – Broken Access Control

Broken Access Control holds the top spot in the OWASP Top Ten for a critical reason: it represents a fundamental failure to enforce policies that restrict users from acting outside their intended permissions. This vulnerability allows attackers to access unauthorised functionality or data, such as viewing other users’ accounts, modifying sensitive files, or elevating their privileges to that of an administrator. The impact directly compromises data confidentiality and integrity.

Real-World Examples and Impact

A practical example of this is an Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR). Imagine a web application for an IoT device that lets you view your device’s data using a URL like https://example.com/device/view?id=123. An attacker could simply change the id parameter to 124 (https://example.com/device/view?id=124). If the server doesn’t verify that the logged-in user actually owns device 124, the attacker gains unauthorized access to another user’s data. For Internet of Things (IoT) devices, the stakes are equally high. A connected security camera with broken access control could allow an unauthenticated user on the local network to access the administrator’s control panel simply by browsing to a specific URL like http://192.168.1.100/admin, enabling them to view live feeds or disable the device entirely.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Detecting and preventing this vulnerability requires a defence-in-depth approach, moving beyond simple obscurity.

Detection Methods:

- Penetration Testing: Manually test for path traversal, privilege escalation, and insecure direct object references (IDORs) by manipulating parameters and URLs.

- Code Analysis: Use static (SAST) and dynamic (DAST) analysis tools to identify access control weaknesses in the codebase and running application.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Principle of Least Privilege: Enforce a “deny by default” policy, where access is only granted explicitly.

- Centralised Control: Implement and enforce access control mechanisms in a single, centralised component. For an IoT device, this means verifying permissions on the server-side or within a secure firmware element, never trusting client-side checks.

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Define clear roles (e.g., ‘user’, ‘administrator’) with specific, documented permissions. This documentation is essential for demonstrating compliance with CRA technical file requirements.

- Rate Limiting: Invalidate access tokens upon logout and limit API access rates to prevent automated attacks.

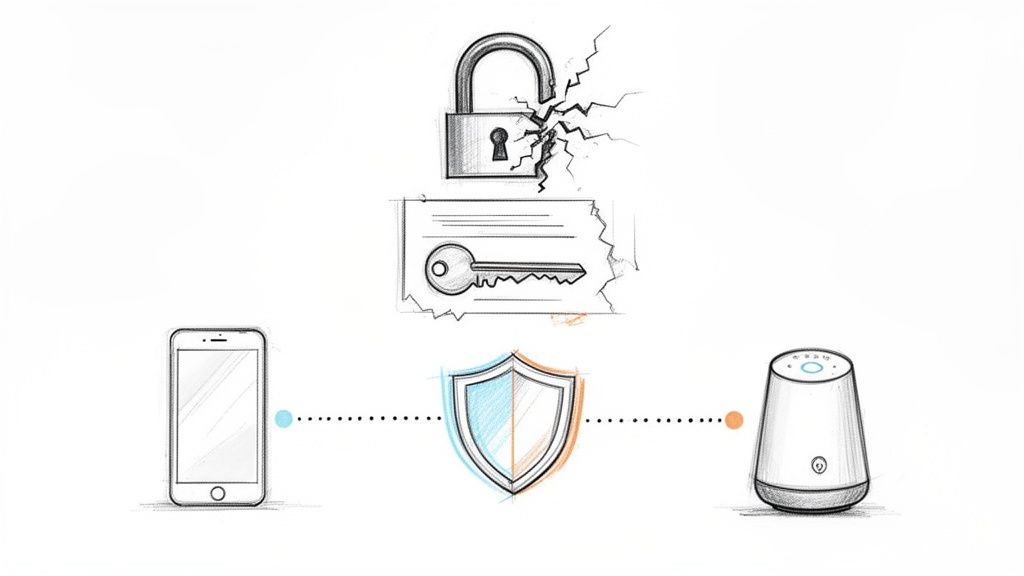

2. A02:2021 – Cryptographic Failures

Cryptographic Failures, ranked second in the OWASP Top Ten, highlight the risks associated with inadequately protecting data. This vulnerability encompasses everything from using weak or outdated encryption algorithms to failing to encrypt sensitive data at all, both in transit and at rest. For manufacturers of connected devices, a cryptographic failure can expose user credentials, compromise firmware update integrity, or leak confidential telemetry data, placing them in direct violation of core security requirements.

Real-World Examples and Impact

The impact of cryptographic failures is severe and widespread. A practical example is a smart thermostat that sends Wi-Fi credentials from a mobile app to the device over an unencrypted HTTP connection. An attacker on the same network can use a simple tool like Wireshark to “sniff” the network traffic and capture the Wi-Fi password in plain text. Similarly, the 2017 Equifax breach was exacerbated by the storage of sensitive data in an unencrypted state. In another IoT context, a smart bulb using weak encryption in its firmware could allow an attacker on the same network to intercept and replay commands, gaining unauthorised control of the device.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

A proactive and rigorous approach to cryptography is essential for building secure and compliant products.

Detection Methods:

- Cryptographic Reviews: Conduct dedicated code and architectural reviews to identify the use of deprecated algorithms, hardcoded keys, or missing encryption for sensitive data flows.

- Penetration Testing: Actively test for weaknesses by attempting to intercept and decrypt network traffic (Man-in-the-Middle attacks) and by analysing firmware for insecurely stored secrets.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Use Strong, Standard Algorithms: Implement only current, industry-accepted cryptographic algorithms like AES-256 for encryption and SHA-256 for hashing, as recommended by bodies like NIST.

- Secure Key Management: Never hardcode cryptographic keys in firmware or software. Utilise hardware security modules (HSMs) or secure enclaves for key storage and management.

- Enforce Secure Transport: Mandate the use of strong transport layer security, such as TLS 1.3, for all data transmitted between a device, its mobile app, and backend servers.

- Document Cryptographic Practices: Maintain clear documentation of all cryptographic protocols, key management procedures, and data protection policies.

3. A03:2021 – Injection

Injection flaws, a long-standing threat in the OWASP Top Ten, occur when untrusted data is sent to an interpreter as part of a command or query. This vulnerability tricks an application into executing unintended commands or accessing data without proper authorisation. For IoT and firmware manufacturers, injection flaws in device interfaces, APIs, or embedded web servers can lead to complete device compromise, unauthorised command execution, and even widespread supply-chain attacks.

Real-World Examples and Impact

The impact of injection attacks on connected devices can be devastating. A classic practical example is a SQL injection attack. If a login form constructs a database query like SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = ' + username + ' AND password = ' + password + ', an attacker can enter ' OR '1'='1 as the username. The resulting query becomes SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '' OR '1'='1' AND password = '...', which always evaluates to true, granting the attacker access without a valid password. In an IoT context, the infamous 2016 Mirai botnet leveraged Telnet and command injection vulnerabilities, exploiting default credentials in routers to create a massive network for launching DDoS attacks.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Preventing injection demands rigorous input validation and adherence to secure coding principles, as mandated by the CRA’s security requirements.

Detection Methods:

- Fuzz Testing: Systematically send malformed and unexpected data to all input fields, APIs, and communication protocols to identify how the system handles it.

- Static and Dynamic Analysis (SAST/DAST): Use automated tools to scan source code for injection patterns and test the running application for vulnerabilities by sending malicious payloads.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Parameterised Queries: Use prepared statements and parameterised queries for all database interactions to ensure user input is treated as data, not executable code.

- Input Validation: Implement strict, whitelist-based validation for all inputs from users, APIs, and other systems. Reject any data that does not conform to the expected format.

- Principle of Least Privilege: Execute all commands and processes with the minimum permissions necessary. For instance, a process handling user input should not have root or administrator privileges.

- Sanitise and Escape Data: Before using any input, sanitise it by removing potentially harmful characters and use context-specific escaping to prevent it from being misinterpreted by an interpreter. This defence-in-depth approach is vital.

4. A04:2021 – Insecure Design

Insecure Design is a new and crucial category in the OWASP Top Ten, representing a broad range of weaknesses that stem from a lack of security-focused design. Unlike implementation bugs, these flaws are architectural and conceptual, meaning they are built into the system before a single line of code is written. For manufacturers creating IoT devices, insecure design can manifest as flawed update mechanisms or inadequate vulnerability handling workflows, directly contradicting core security-by-design principles.

Real-World Examples and Impact

Architectural design flaws are often expensive to fix and can have catastrophic consequences. A practical example is a password reset feature that asks a “secret question” whose answer is easily discoverable through public sources, such as “What is your mother’s maiden name?”. A better design would email a single-use, time-limited reset link. Similarly, the widespread AWS S3 bucket misconfigurations of 2019 were a result of a default-insecure design, leading to millions of exposed records across countless organisations because security was not the default state. These examples highlight how foundational design decisions, not just coding errors, can lead to severe security breaches.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Addressing insecure design requires a proactive shift towards a “secure-by-design” culture, embedding security into the entire product lifecycle.

Detection Methods:

- Threat Modelling: Proactively conduct threat modelling during the design phase using frameworks like STRIDE to identify and analyse potential threats to the system architecture.

- Design Reviews: Perform rigorous security architecture reviews against established checklists and security requirements before development begins.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Establish a Secure Development Lifecycle: Integrate security practices at every stage of development. This approach is fundamental to building resilient systems and demonstrating compliance. For detailed guidance, explore the principles of a CRA Secure Development Lifecycle (SDL).

- Define Security Requirements: Explicitly document security requirements, such as encryption standards and access control policies, within product specifications.

- Security by Default: Ensure all default configurations are secure. For instance, an IoT device should ship with strong, unique credentials and have all unnecessary ports closed by default.

- Plan for Failure: Design secure update mechanisms with integrity verification and rollback capabilities. Plan vulnerability disclosure and handling workflows from the project’s inception.

- Documentation: Create comprehensive security architecture documentation as part of the technical file to meet regulatory requirements like the CRA.

5. A05:2021 – Security Misconfiguration

Climbing from sixth to fifth place in the OWASP Top Ten, Security Misconfiguration refers to flaws arising from improperly configured security controls or insecure default settings. For IoT and embedded systems, this vulnerability can manifest across the entire product stack, from an unsecured bootloader and open debugging ports to an embedded web server running with default credentials. It often happens when security settings are overlooked during development, deployment, or maintenance, creating an easy entry point for attackers.

Real-World Examples and Impact

History is filled with incidents caused by simple configuration errors. A practical example is an IoT device that ships with a debugging interface like a JTAG or UART port physically accessible and enabled in the production firmware. An attacker with physical access could connect to this port and gain root access to the device, extract firmware, and steal cryptographic keys. In the IoT world, a 2018 Shodan search indexed thousands of devices, including industrial control systems, that were accessible online using default SSH credentials like “admin/admin”. Similarly, numerous MongoDB ransomware incidents stemmed from databases left unsecured with default settings that allowed open network access, leading to widespread data loss and extortion.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Preventing security misconfiguration requires a systematic and repeatable process for hardening every component of a system.

Detection Methods:

- Vulnerability Scanning: Use automated scanners to check for open ports, default credentials, and outdated software versions on both production and development systems.

- Configuration Review: Manually and automatically audit system configurations against established security benchmarks like those from the Center for Internet Security (CIS).

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Secure Baselines: Create and maintain hardened, secure configuration templates for all firmware images and deployed products. This baseline should be a key part of your technical documentation.

- Minimalism by Default: Disable all unnecessary features, services, and ports in the default configuration. Only enable what is explicitly required for the device’s functionality.

- Forbid Default Credentials: Mandate that users change all default passwords upon the first boot of a device. Never ship products with hardcoded or easily guessable credentials.

- Automated Auditing: Implement configuration management tools to continuously track, audit, and remediate any configuration drift from your secure baseline across the entire product fleet. This process is a vital component of a comprehensive CRA risk assessment.

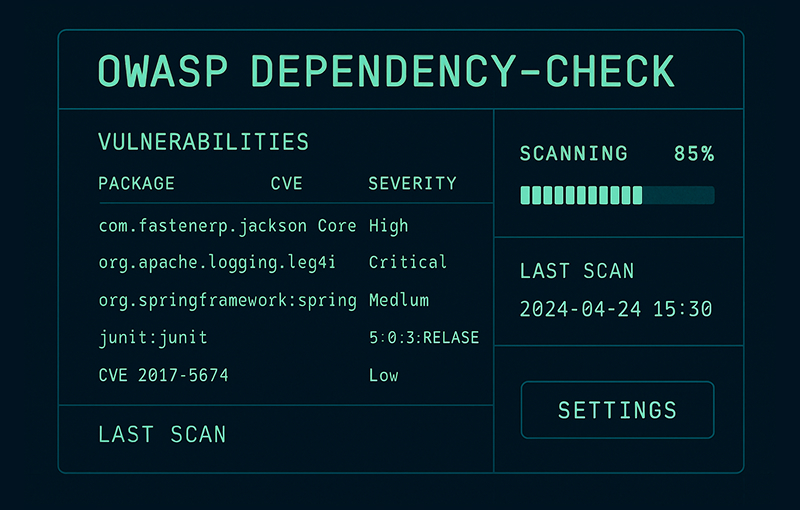

6. A06:2021 – Vulnerable and Outdated Components

This vulnerability, often referred to as supply chain risk, occurs when a product relies on libraries, frameworks, or other software components with known security flaws. It holds a prominent place in the OWASP Top Ten because modern development is heavily dependent on third-party code. For IoT manufacturers, this is particularly critical as devices are often deployed for years, making them susceptible to newly discovered vulnerabilities in unpatched components.

Real-World Examples and Impact

The impact of a single vulnerable component can be catastrophic, affecting millions of devices globally. The infamous Log4Shell vulnerability (CVE-2021-44228) in the Apache Log4j library is a prime example. This flaw allowed for remote code execution and affected countless applications and embedded systems, forcing widespread and urgent patching efforts. A more practical, everyday example is a smart camera that uses an old version of the OpenSSL library with a known vulnerability like Heartbleed. An attacker could exploit this flaw to steal sensitive information from the device’s memory, such as private keys or user credentials, without leaving a trace.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Addressing this risk requires a systematic approach to software supply chain management, moving from a reactive to a proactive security posture.

Detection Methods:

- Software Composition Analysis (SCA): Use automated tools like OWASP Dependency-Check, Snyk, or Black Duck to scan dependencies and identify known vulnerabilities.

- SBOM Analysis: Regularly generate and review a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) to maintain a complete inventory of all components and their versions.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Maintain a Comprehensive SBOM: Create and continuously update a detailed SBOM for all products. This is not just a best practice; it is a core documentation requirement under the EU’s Cyber Resilience Act. You can find more details on how to meet these obligations by reading about CRA SBOM requirements.

- Establish a Patching Policy: Define and enforce strict timelines for applying security updates. For instance, remediate critical vulnerabilities within a short, defined period and regularly patch other known issues.

- Automated Dependency Scanning: Integrate SCA tools directly into your CI/CD pipeline to block builds that introduce components with high-severity vulnerabilities.

- Component Lifecycle Management: Track end-of-life dates for all dependencies and plan for their replacement or migration to avoid being stuck with unsupported, insecure code.

- Supplier Vetting: Conduct a risk assessment for all third-party software suppliers, evaluating their security practices and responsiveness to vulnerability reports.

7. A07:2021 – Identification and Authentication Failures

Identification and Authentication Failures encompass a broad range of weaknesses related to confirming user identity. This category, a crucial part of the OWASP Top Ten, highlights how improperly implemented authentication can allow attackers to compromise passwords, keys, or session tokens to assume other users’ identities. For connected devices, this could mean an attacker gaining control of a device, tampering with its firmware, or intercepting sensitive data streams.

Real-World Examples and Impact

Weak authentication has been the root cause of many high-profile incidents. A very common practical example is a website that allows weak passwords (e.g., “123456” or “password”) and does not implement rate limiting on login attempts. An attacker can perform a “brute-force” attack, using automated scripts to try millions of common passwords until they find the correct one. In 2019, weak password policies for Ring doorbells led to widespread “credential stuffing” attacks, where attackers used leaked credentials from other breaches to gain access to user accounts and camera feeds. For an IoT device manufacturer, a default, easily guessable admin password could allow an attacker to take over thousands of devices on a network.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Robust authentication is a foundational pillar of security, requiring layers of defence and proactive testing.

Detection Methods:

- Credential Stuffing Tests: Attempt to log in with lists of known weak or breached passwords to identify vulnerable accounts.

- Vulnerability Scanning: Use automated tools to check for weak password policies, missing brute-force protections, and insecure session management.

- Manual Penetration Testing: Actively try to bypass authentication flows, exploit password reset functions, and hijack user sessions.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Implement and encourage MFA for all user accounts, and make it mandatory for administrative and privileged access.

- Strong Password Policies: Enforce minimum length (12+ characters), complexity, and a check against known breached passwords. Implement account lockout and progressive delays after multiple failed login attempts.

- Secure Credential Storage: Never store passwords in clear text or use weak hashing algorithms. Use strong, salted, and peppered hashing functions like Argon2 or bcrypt. For devices, never hardcode credentials in firmware.

- Secure Session Management: Generate unique, high-entropy session tokens upon login. Ensure they are invalidated upon logout, idle timeout, and are transmitted over secure channels.

- Device-to-Server Authentication: Use strong, unique-per-device credentials like X.509 certificates for secure communication, and implement certificate pinning to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks.

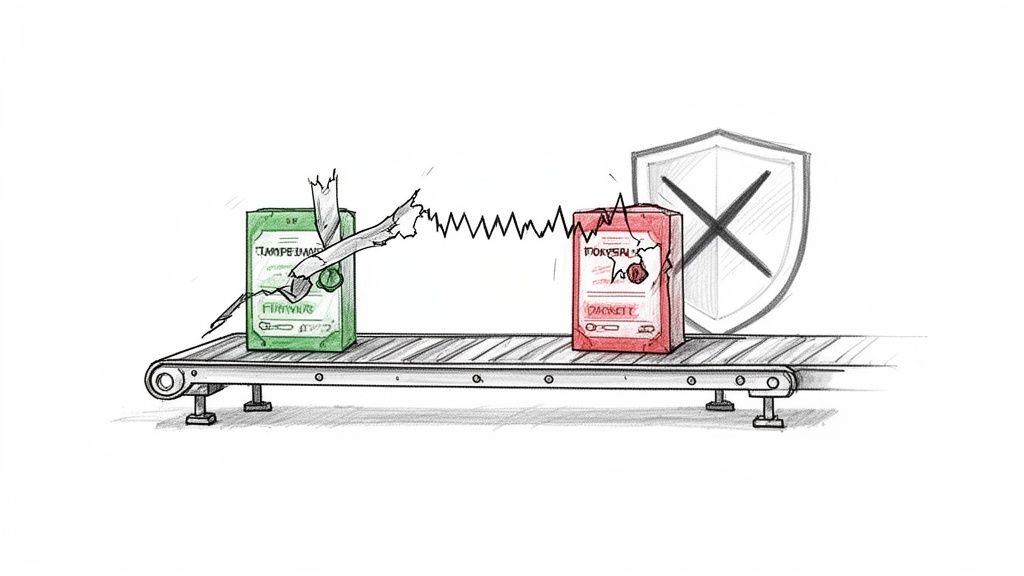

8. A08:2021 – Software and Data Integrity Failures

This category in the OWASP Top Ten focuses on failures related to verifying the integrity of software updates, critical data, and CI/CD pipelines. These vulnerabilities arise when an application relies on plugins, libraries, or modules from untrusted sources, repositories, and CDNs without proper validation. For manufacturers of firmware and IoT devices, these failures can lead to devastating supply-chain attacks, where malicious code is injected into legitimate updates, compromising entire fleets of deployed products.

Real-World Examples and Impact

The SolarWinds attack of 2020 is a prime example of a software integrity failure, where attackers compromised the build environment to inject malicious code into a legitimate software update. A more direct practical example for an IoT device is an Over-The-Air (OTA) update mechanism that downloads a firmware update over HTTP without checking its digital signature. An attacker on the same network could perform a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attack, intercept the download request, and serve a malicious firmware file instead. Since the device doesn’t verify the file’s integrity, it would install the malicious firmware, giving the attacker complete control. This is precisely what researchers demonstrated with the 2015 Jeep Cherokee hack.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Ensuring the integrity of your software supply chain is non-negotiable, especially under regulatory frameworks like the CRA, which mandate secure update mechanisms.

Detection Methods:

- Pipeline Audits: Regularly audit your build and deployment pipelines to ensure all dependencies are fetched from trusted sources and their integrity is checked using hashes.

- Binary Analysis: Use software composition analysis (SCA) tools to identify components with known vulnerabilities and analyse firmware binaries for unexpected modifications.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Cryptographic Code Signing: Sign all firmware and software updates with strong digital signatures (e.g., ECDSA). The device must verify this signature before applying any update.

- Secure Boot: Implement a secure boot chain where each stage of the boot process cryptographically verifies the integrity of the next, ensuring the device only runs trusted code.

- Protected Update Channels: Deliver updates exclusively over secure, authenticated channels like HTTPS with certificate pinning to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Rollback Protection: Prevent attackers from downgrading a device to an older, vulnerable firmware version by implementing anti-rollback mechanisms.

- Documentation: Your CRA technical file must detail the entire firmware signing, verification, and secure distribution process as proof of compliance.

9. A09:2021 – Security Logging and Monitoring Failures

Previously known as Insufficient Logging & Monitoring, this vulnerability secures a spot in the OWASP Top Ten because without visibility, organisations are blind to attacks. This category highlights failures to adequately log security-relevant events, monitor for suspicious activity, or respond to incidents in a timely manner. For connected device manufacturers, this weakness means an attack, such as unauthorised firmware modification or a widespread credential stuffing campaign, could go completely unnoticed until it’s too late.

Real-World Examples and Impact

History is filled with breaches that were prolonged by monitoring failures. A practical example is a web application that logs failed login attempts but doesn’t generate any alerts. An attacker could run a brute-force script that tries thousands of passwords per hour. The failed attempts are recorded in a log file, but since no one is monitoring those logs or receiving alerts about the high rate of failures from a single IP address, the attack continues undetected until it succeeds. In the infamous 2013 Target breach, attackers exfiltrated data for weeks, yet the security alerts generated by their activity were ignored or missed, ultimately exposing 40 million credit card details.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

A robust logging and monitoring framework is the central nervous system of a secure product, enabling detection, response, and forensic analysis.

Detection Methods:

- Audit and Review: Manually review the application and its infrastructure to verify that all critical security events are being logged in a consistent, usable format.

- Breach Simulation: Conduct penetration tests or red team exercises specifically designed to see if the attack activities are detected and trigger the appropriate alerts.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Log Critical Events: Ensure all authentication attempts (both successful and failed), access control decisions, and administrative changes are logged with user context, timestamps, and source IPs.

- Centralised and Protected Logs: Aggregate logs in a centralised, secure location. Implement measures like log signing or append-only storage to protect their integrity against tampering.

- Real-Time Alerting: Configure automated alerts for high-risk events, such as multiple failed login attempts from a single IP, unexpected configuration changes, or attempts to access critical system files.

- Establish Response Plans: Develop and test incident response procedures that are directly triggered by monitoring alerts to ensure a swift and effective reaction to potential threats. Documenting this framework is a key part of demonstrating compliance; learn more about logging and monitoring requirements under the CRA.

10. A10:2021 – Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) is a vulnerability that tricks a server-side application into making HTTP requests to an arbitrary domain of the attacker’s choosing. This flaw arises when an application fetches a remote resource using a user-supplied URL without properly validating it. An attacker can exploit this to pivot through the application server, bypass firewalls, and interact with internal, non-public services, effectively using the server as a proxy to attack the internal network.

Real-World Examples and Impact

SSRF has been the root cause of several high-profile breaches, demonstrating its critical impact. A simple practical example is a feature that allows a user to import a profile picture by providing a URL. If the server fetches whatever URL is provided, an attacker can supply an internal IP address like http://192.168.0.1/admin. The server, which is inside the firewall, will make a request to that internal admin panel, potentially revealing sensitive information. In an IoT context, an attacker could exploit an SSRF flaw in a smart home hub’s web interface to send commands to other devices on the local network, such as unlocking smart locks or accessing security camera feeds that were never meant to be exposed externally.

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Preventing SSRF requires strict control over how an application handles outbound requests initiated by user input, a key concern in the OWASP Top Ten.

Detection Methods:

- External Service Interaction: Use tools that can detect out-of-band network interactions, providing a unique URL to the application and monitoring for any requests made to it.

- Code Review: Manually inspect code and perform static analysis (SAST) on any function that parses URLs or makes server-side requests based on user input.

Mitigation and Secure-by-Design:

- Validate and Sanitise Input: Never trust user-supplied URLs. Implement a strict allowlist of authorised domains, IP addresses, and protocols. Deny all other requests by default.

- Network Segmentation: Isolate the application server in a restricted network segment with strict firewall rules that prevent it from making connections to internal services.

- Disable Unused URL Schemas: Only permit necessary protocols like

httpandhttps, and explicitly disable dangerous ones such asfile://,gopher://, anddict://to prevent local file access or other attacks. - Unified Request Handling: Route all outbound requests through a single, hardened component that enforces validation and logging, which helps in demonstrating secure design for CRA compliance.

OWASP Top 10 Vulnerabilities Comparison

| Item | Implementation complexity | Resource requirements | Expected outcomes | Ideal use cases | Key advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A01:2021 – Broken Access Control | High — requires architecture & RBAC changes | Moderate–High — audits, testing, logging | Prevents unauthorized actions; protects confidentiality/integrity | Multi-tenant systems, device management, admin consoles | Foundational for compliance; prevents privilege escalation |

| A02:2021 – Cryptographic Failures | Medium–High — secure algorithms & key management | High — HSMs/secure enclaves, key lifecycle, CPU overhead | Ensures confidentiality and integrity of data & updates | Firmware updates, telemetry, device authentication | Strong crypto enforces supply-chain and CRA requirements |

| A03:2021 – Injection | Medium — input validation & parameterization | Low–Medium — dev effort, testing/fuzzing tools | Prevents arbitrary code/DB/OS execution and data leaks | APIs, embedded web servers, command interfaces | Well-documented mitigations; many automated detectors |

| A04:2021 – Insecure Design | High — requires design-phase security changes | High — security expertise, cross-functional coordination | Reduces systemic vulnerabilities and future rework | New product architecture, OTA/update design | Prevents costly fixes later; aligns with CRA documentation |

| A05:2021 – Security Misconfiguration | Low–Medium — baselines and deployment controls | Medium — config management, audits, automation | Reduces exposure from defaults and drift | Device provisioning, production deployments, servers | Often easier to remediate; automatable detection |

| A06:2021 – Vulnerable & Outdated Components | Medium — SBOM, dependency tracking, patching | High — supply-chain tracking, update channels | Faster response to CVEs; reduced supply-chain risk | Long-lived devices, third-party libs, SDKs | SBOMs and scanners improve visibility and compliance |

| A07:2021 – Identification & Authentication Failures | Medium — implement MFA, secure sessions | Medium–High — auth infrastructure, cert management | Reduces account and device compromise risk | Admin interfaces, device enrollment, user accounts | Standardized controls (MFA, OAuth) strongly effective |

| A08:2021 – Software and Data Integrity Failures | Medium–High — code signing, secure boot, CI hardening | High — key mgmt, signing infrastructure, hardware support | Prevents supply-chain tampering and malicious updates | Firmware update pipelines, CI/CD, build servers | Strong assurance via signatures; CRA-mandated for updates |

| A09:2021 – Logging and Monitoring Failures | Low–Medium — instrumenting and aggregating logs | Medium — storage, SIEM, analysts, retention policies | Enables detection, forensics, and timely incident response | Post-market surveillance, incident investigations | Essential for auditability and CRA incident reporting |

| A10:2021 – Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) | Low–Medium — URL validation and network controls | Low–Medium — allowlists, segmentation, timeouts | Prevents server from being used to reach internal resources | Services fetching external resources, cloud metadata access | Straightforward mitigations; reduces lateral movement risk |

From Awareness to Action: Operationalising CRA Compliance with Regulus

Navigating the landscape of modern cybersecurity can feel like a monumental task, but as we have explored, the OWASP Top Ten provides an essential, community-driven roadmap. It transforms abstract security principles into a tangible framework, guiding developers and manufacturers away from the most critical and common pitfalls. Throughout this article, we have dissected each of the ten vulnerabilities, moving beyond mere definitions to provide real-world examples, particularly in the challenging context of IoT and embedded systems. We’ve seen how a simple oversight in access control (A01) can grant an attacker administrative privileges on a smart home hub, or how outdated components (A06) in a medical device’s firmware can leave sensitive patient data exposed.

The key takeaway is that these vulnerabilities are not isolated technical glitches; they are systemic risks with profound consequences. A cryptographic failure (A02) is not just a coding error, it’s a breach of user trust. An insecure design (A04) is not a minor oversight, it’s a foundational flaw that invites exploitation. Understanding the OWASP Top Ten is the crucial first step, but true security maturity-and compliance with stringent regulations like the EU’s Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)-demands a shift from awareness to sustained, operationalised action.

Bridging the Gap Between Security Principles and Regulatory Mandates

The principles enshrined in the OWASP Top Ten are no longer just best practices; they are becoming legal obligations. The Cyber Resilience Act directly codifies many of these concepts into law for any product with digital elements placed on the EU market. For instance:

- Vulnerability Management (CRA Article 10): This aligns directly with A06: Vulnerable and Outdated Components. Manufacturers are mandated to have processes for identifying and remediating vulnerabilities in third-party components throughout the product’s support lifecycle.

- Secure by Default (CRA Annex I): This requirement is a direct reflection of A05: Security Misconfiguration. Products must be delivered to users with a secure configuration out of the box, minimising the attack surface from the moment of deployment.

- Protection of Data Integrity (CRA Annex I): This mirrors the concerns of A08: Software and Data Integrity Failures. The CRA demands mechanisms to ensure that software, firmware, and data are protected from unauthorised modification, a core tenet of building resilient systems.

The challenge for manufacturers, especially those with extensive product portfolios or complex supply chains, is translating these high-level principles into verifiable, documented evidence of compliance. Manually tracking which OWASP control mitigates which CRA requirement for every single product is an inefficient, error-prone process that simply does not scale.

A Structured Path to Compliance

To successfully navigate this new regulatory environment, organisations must adopt a structured and automated approach. The journey from understanding the OWASP Top Ten to achieving demonstrable CRA compliance involves several critical steps. It begins with establishing a secure development lifecycle, where security is a consideration from the initial design phase (addressing A04: Insecure Design) all the way through to post-market surveillance and vulnerability handling.

This requires robust internal processes for everything from secure coding and testing (to catch issues like A03: Injection) to comprehensive logging and monitoring (to satisfy A09 and CRA incident reporting rules). The goal is to embed these security practices so deeply into your workflow that they become second nature, not a last-minute compliance checklist. This is where a dedicated platform becomes indispensable. Instead of grappling with sprawling spreadsheets and disparate documents, a centralised system can map security controls to regulatory obligations, automate evidence collection, and provide a clear, auditable trail of your compliance efforts. By operationalising security, you transform it from a cost centre into a strategic advantage, building more resilient products and earning the trust of your customers in a competitive market.

Ready to move beyond spreadsheets and operationalise your CRA compliance strategy? Regulus provides a centralised platform to manage your product security, map requirements from the OWASP Top Ten directly to CRA obligations, and build your technical file with confidence. Discover how you can automate your compliance journey at Regulus.